An article to understand the Internet of Things - what is the Internet of Things? Everything you need to know about the Internet of Things now

What is the Internet of Things?

The Internet of Things (IoT) refers to the billions of physical devices around the world that are now connected to the internet, collecting and sharing data. Thanks to cheap processors and wireless networks, it is possible to turn anything, from pills to airplanes, into part of the Internet of Things. This adds a level of digital intelligence to those unwieldy devices, allowing them to communicate without human involvement and to merge the digital and physical worlds.

What are examples of IoT devices?

Any physical object can be transformed into an IoT device if it can be connected to the internet and controlled in this way.

A light bulb that can be turned on with a smartphone app is an IoT device, a motion sensor or smart thermostat in your office, or a connected street light. IoT devices, which can be as fluffy as a child's toy, as serious as a driverless truck, or as sophisticated as a jet engine, are now filled with thousands of sensors that collect and transmit data. On a larger scale, smart city projects are spreading sensors throughout regions to help us understand and control our environment.

The term "Internet of Things" is used primarily for devices that typically do not require a network connection, and can communicate with the network independently of human actions. For this reason, PCs aren't usually considered IoT devices, nor are smartphones -- despite the latter's chock-full of sensors. However, a smartwatch or fitness band might be considered an IoT device.

What is the history of IoT?

During the 1980s and 1990s, the idea of adding sensors and intelligence to basic objects was discussed (and arguably had some earlier ancestors), but apart from a few early projects, including an Internet-connected automated For vending machines, the progress is slow and the technology is not in place.

Processors are so cheap and low-effort that they can all but be thrown away, so processors are needed before billions of devices are connected to become cost-effective. The RFID tags use low-power chips that can communicate wirelessly -- solving some of this problem, along with the growing popularity of broadband networks and cellular and wireless networks. Among other things, the adoption of IPv6 should also provide enough IP addresses for each device (or what this galaxy might need), a necessary step for the expansion of the Internet of Things. Kevin Ashton coined the term "Internet of Things" in 1999, though it will be at least a decade before the technology catches up to the vision.

“The Internet of Things combines the interconnectedness of human culture – our “things” with the interconnectedness of our digital information system – the Internet. This is the Internet of Things,”

Adding RFID tags to expensive devices to help track their location is one of the earliest IoT applications. But since then, the cost of adding sensors and internet connectivity to objects has been falling, and experts predict that this basic functionality could one day cost as little as 10 cents, allowing nearly everything to be connected to the internet.

The Internet of Things was originally favored mostly by business and manufacturing, and its applications are sometimes referred to as machine-to-machine (M2M), but the focus now is on filling our homes and offices with smart devices, turning them into something relevant to virtually everyone. . Early proposals for Internet-connected devices included "blogs" (objects that blog and record data about themselves on the Internet), ubiquitous computing (or "ubicomp"), invisible computing, and ubiquitous computing. However, the Internet of Things and the Internet of Things are in trouble.

How big is the Internet of Things?

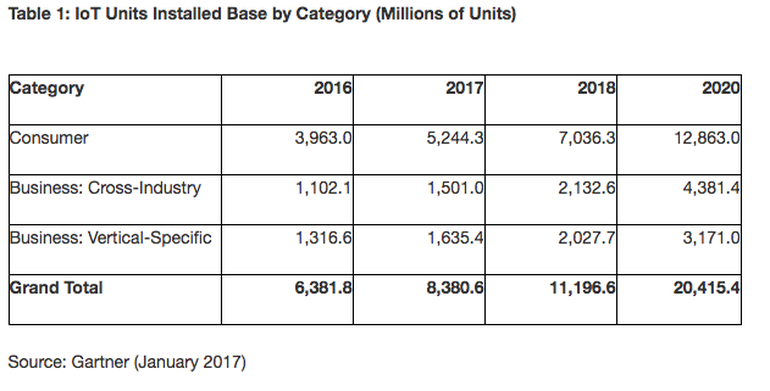

Getting Bigger - There are already more people connected than there are in the world. Analyst Gartner estimates that some 8.4 billion IoT devices were in use in 2017, a 31 percent increase from 2016, and could reach 20.4 billion by 2020. Total spending on IoT endpoints and services will reach nearly $2 trillion in 2017, with two-thirds of those devices located in China, North America and Western Europe, Gartner said.

Of those 8.4 billion devices, more than half will be consumer products like smart TVs and smart speakers. According to Gartner, the most commonly used enterprise IoT devices will be smart meters and commercial security cameras.

Worldwide spending on IoT will reach $772.5 billion in 2018, up nearly 15 percent from $674 billion in 2017, according to another IDC analyst. IDC predicts total spending will reach $1 trillion in 2020 and $1.1 trillion in 2021.

According to IDC, hardware will be the largest technology category in 2018, with usage of modules and sensors reaching $239 billion, with some spending on infrastructure and security. Services will be the second largest technology category, followed by software and connectivity.

What are the benefits of IoT for business?

Sometimes referred to as the Industrial Internet of Things (IoT), the business benefits of IoT depend on the specific implementation, but the key is that companies should have access to more data about their own products and their own internal systems, so they can make changes.

Manufacturers are adding sensors to their product components so they can send back data about how they are performing. This can help companies spot when a component might be failing and swap it out before it breaks. Companies can also use the data generated by these sensors to make their systems and supply chains more efficient as they will have more accurate data.

Consultants McKinsey (McKinsey) said: "With the introduction of comprehensive, real-time data collection and analysis, the responsiveness of production systems will be greatly improved.

Enterprise use of IoT can be broken down into two segments: industry-specific products such as sensors in power plants or real-time location devices for healthcare; and IoT devices that can be used in all industries, such as smart air conditioners or security systems.

While industry-specific products will run ahead, by 2020, Gartner forecasts 4.4 billion units of cross-industry devices and 3.2 billion units of vertical-specific devices. Consumers are buying more devices, but businesses are spending more: Consumer spending on IoT devices was about $725 billion last year, with business spending on IoT reaching $964 billion, the analyst group said. IoT hardware business and consumer spending will reach nearly $3 trillion by 2020.

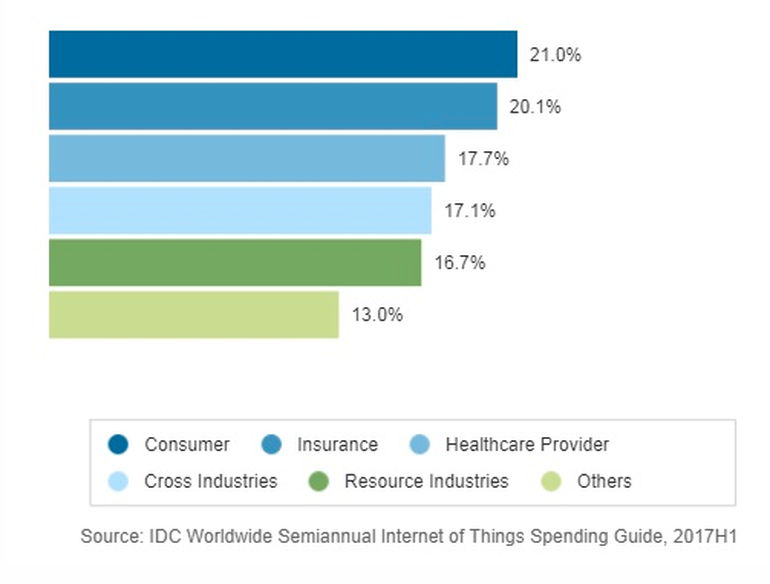

Internet of Things, segmented by industry.

For IDC, the three industries expected to spend the most on IoT in 2018 are manufacturing ($189 billion), transportation ($85 billion) and utilities ($73 billion). Manufacturers will focus primarily on improving the efficiency of processes and asset tracking, while two-thirds of transportation IoT spending will go to freight monitoring, followed by fleet management.

IoT spending in the power sector will be dominated by smart grids for electricity, gas and water. IDC spent nearly $92 billion in 2018 on cross-industry IoT areas such as connected cars and smart buildings.

What are the benefits of IoT for consumers?

The Internet of Things promises to make our environments—our homes, offices, and vehicles—smarter, more measurable, and more beautiful. Smart speakers like Amazon's Echo and Google Home make it easier to play music, set timers or get information. A home security system makes it easier to monitor what's happening inside and outside, or to communicate with visitors. Meanwhile, smart thermostats can help us heat our homes before we get home, and smart light bulbs can help us look like home even when we’re out.

Looking around, sensors can help us understand the likelihood of noise or polluted environments. Autonomous cars and smart cities could change the way we build and manage public spaces.

However, many of these innovations could have significant implications for our personal privacy.

IoT and Smart Home

The house built by Alexa: Amazon showcase in London, 2017.

For consumers, the smart home is one of the things they're likely to touch the internet, and it's one of the areas where the big tech companies, notably Amazon, Google and Apple, are fiercely contested.

The most obvious of these are smart speakers like the Amazon Echo, but there are also smart plugs, light bulbs, cameras, thermostats, and, mockingly, smart refrigerators. But beyond showing off your enthusiasm for new gadgets, smart home apps have a more grim side. By making it easier for family members and caregivers to communicate with them and monitor how they work, they may be able to help older adults become independent and maintain their own time at home. For example, a better understanding of how our homes function and the ability to adjust these environments can help save energy, for example by reducing heating costs.

What about IoT security?

Security is one of the biggest concerns of IoT. In many cases, these sensors collect extremely sensitive data – for example, what you say and do in your own home. Staying secure is critical to consumer trust, but IoT has had an abysmal security record thus far. Too many IoT devices have little thought for the basics of security, like encrypting data in transit and at rest.

Flaws in software – even in old and used code – are discovered on a regular basis, but the lack of patching capabilities for many IoT devices means they are always at risk. Hackers are now actively targeting IoT devices such as routers and webcams because their inherent insecurity makes them easy to compromise and become involved in giant botnets.

Smart home devices like refrigerators, ovens and dishwashers are open to hackers. Researchers have found that 100,000 webcams can be easily hacked, while some internet-connected smartwatches for kids have been found to have security flaws that allow hackers to track the wearer's location, eavesdrop on conversations, and even communicate with users.

These problems will only become more widespread and intractable if the cost of smart devices becomes trivial.

The Internet of Things bridges the gap between the digital and physical worlds, meaning hacking into devices can have dangerous real-world consequences. Hacking the sensors that control the temperature of a power station could trick operators into making disastrous decisions; taking control of a driverless car could end in disaster, too.

What about privacy and the Internet of Things?

All of these sensors collect data about everything you do, so IoT is a potentially huge privacy concern. Take the smart home: it can tell when you wake up (when the smart coffee machine is activated), how well you brush your teeth (thanks to your smart toothbrush), what radio station you listen to (thanks to your smart speaker), what you eat What types of food are served (thanks to your smart oven or fridge), what are your kids thinking (thanks to their smart toys), who visits you and passes by your house (thanks to your smart doorbell).

What happens to this data is a very important privacy issue. Not all smart home companies have built their business models around harvesting and selling data, but some do. It's very easy to discover a lot about a person from a few different sensor readings. In one project, a researcher found that by analyzing the data, energy consumption, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide levels, temperature and humidity in a home could be calculated, and throughout the day they could figure out who had dinner.

Consumers need to know what they are exchanging and whether they are satisfied. Some of the same questions apply to business: For example, would your executive team be comfortable discussing a merger in a conference room equipped with smart speakers and video cameras? A recent survey found that five out of four companies will not be able to identify all IoT devices on their network.

Internet of Things and Cyber Warfare

IoT makes computing physics. So if something goes wrong with an IoT device, there could be major real-world consequences – countries are planning their cyber warfare strategies, and are thinking about it now.

Last year, a U.S. intelligence agency briefing warned that the country's adversaries had the capability to threaten its critical infrastructure, as well as "the broader ecosystem of connected consumer and industrial devices known as the Internet of Things." U.S. intelligence agencies have also warned that connected thermostats, cameras and cookers could all be used to spy on citizens of another country, or wreak havoc if they were hacked. Adding key elements of the nation's critical infrastructure, such as dams, bridges, and grid elements, to the Internet of Things makes security increasingly tight, which is even more important.

IoT and Big Data

The Internet of Things generates vast amounts of data: from sensors connected to machine parts or environmental sensors, or the words we shout on our smart speakers. This means IoT is an important enabler for big data projects as it allows companies to create massive data sets and analyze them. Giving manufacturers a wealth of data about how their components behave in real-world environments can help them make improvements faster, while data from sensors around cities can help planners implement traffic flow more efficiently.

In particular, IoT will provide massive amounts of real-time data. Cisco calculates that machine-to-machine connections supporting IoT applications will account for more than half of the total 27.1 billion devices and connections, and five percent of global IP traffic by 2021.

IoT and Cloud

The sheer volume of data generated by IoT applications means that many companies will choose to do data processing in the cloud, rather than building massive in-house capacity. The cloud giants are already courting these companies: Microsoft has its Azure IoT suite, while Amazon Web Services offers a range of IoT services, as does Google Cloud.

Internet of Things and Smart Cities

By spreading a large number of sensors across a town or city, planners can see in real time what is really happening. Therefore, smart city projects are a key feature of IoT. Cities already generate vast amounts of data (from security cameras and environmental sensors) and already contain large infrastructure networks (such as those that control traffic lights). IoT projects aim to connect these and then add more intelligence to the system.

For example, there are plans to cover half a million sensors with the Spanish Balearic Islands, turning them into laboratories for IoT projects. One scenario might involve regional social services using sensors to help older people, while another could determine if a beach is getting too crowded and offer substitute swimmers. In another example, AT&T is launching a service to monitor infrastructure such as bridges, roads and railroads using LTE-enabled sensors to detect structural changes such as cracks and tilt.

The ability to better understand how a city works should allow planners to make changes and monitor how that improves the lives of residents.

Big tech sees smart city projects as a potentially huge field, and many companies, including mobile operators and network companies, are now stepping in themselves.

How are IoT devices connected?

IoT devices use a variety of methods to connect and share data: homes and offices will use standard Wi-Fi or Bluetooth Low Energy (or even Ethernet if they're not particularly mobile); other devices will communicate using LTE or even satellite connections . But the multitude of different options has led some to argue that an IoT communication standard needs to be accepted and interoperable like Wi-Fi.

One likely trend is that as the Internet of Things grows, there may be less data being sent to the cloud for processing. To keep costs down, more processing can be done on the device, sending only useful data back to the cloud – a strategy known as "edge computing".

Where is the Internet of Things next?

As the prices of sensors and communications continue to drop, it becomes more cost-effective to add more devices to the IoT – even in some cases where there is little discernible benefit to consumers. As the number of connected devices continues to increase, our living and working environments will be filled with smart gadgets – assuming we're willing to accept the security and privacy trade-offs. Some will welcome a new age of smart things. When a chair is just a chair, everyone else looses up.